The Persian Palms

Today’s guest blogger is James Eli Shiffer, author of the newly published book, The King of Skid Row: John Bacich and the Twilight Years of Old Minneapolis.

If Minneapolis were to create a dive bar hall of fame, the Persian Palms would be the first inductee. A bland office block now sits at 109-111 Washington Avenue. But back in the 1950s, the three story brick building with the garish marquee on this site sounded a siren song to both habitual drinkers and upright citizens, who risked body and wallet to revel in its free-flowing liquor and transgressive sexuality. Like Moby Dick’s, Stand Up Frank’s and other vanished venues, this bar was a notorious landmark in a city deeply conflicted about alcohol and sex.

The bar cultivated a salacious appeal that drew customers from far and wide. People from all over the region knew the Persian Palms as a place to defy 1950s-era expectations of respectability. They could walk on the wild side at this strip joint, which was known for its live and sometimes bizarre entertainment. The bar advertised “three floor shows nightly.” One city alderman called the Palms “one of the raunchiest joints in town.”

The Persian Palms was in many ways the fake jewel in the tarnished crown of the Minneapolis Gateway District, the heart of the old city where Hennepin, Nicollet and Washington Avenues came together. The Gateway was the region’s largest Skid Row, home to thousands of retired or disabled laborers, drunks, loners and lost souls.

Streetscape showing the Persian Palms in the Minneapolis Gateway District, shortly before its demolition. Image is from the Hennepin History Museum.

The sale of liquor was banned in most Minneapolis neighborhoods until 1974. Alcohol was concentrated in the city’s 20-block Gateway district, which was awash in saloons, beer parlors and liquor stores. Researchers counted 62 of them in 1952. Most were shunned by anyone who lived outside the neighborhood. Few remember the Pastime Bar, the Old Bowery, the White Star Saloon, the Hub or the Valhalla. These were pedestrian purveyors of liquor, utilitarian service stations for men determined to drink the most they could for the least amount of money.

The Persian Palms was something else altogether.

Since I published a book this spring about the last years of Minneapolis’ notorious Skid Row, everyone I meet seems to want to talk about the Persian Palms. One man told me his late great-uncle was the manager of the place. Another one told me his uncle Clyde used to drink himself into oblivion there, and would occasionally have to be dragged out, dried up and sent back home to Rochester. Another recalled a troupe of plus-sized dancers at Palms that performed weekly can-can routines. They were known as the Beef Trust Chorus, somewhat of a fad at the time, and its “captain,” Violet Morton, tipped the scales at more than 300 pounds.

Violet Morton, Captain, Beef Trust Chorus. Persian Palms, January 18, 1951. Image is from the Minneapolis Star Tribune and is used with permission. All rights reserved.

One woman wrote me a letter recalling a visit to the bar in September 1950. She ordered a beer so she wouldn’t have to drink from the glasses of questionable cleanliness. The main attraction that night was Divena, a stripper who performed underwater, in a very large fish-tank. It wasn’t especially sexy, but memorable nonetheless, she wrote.

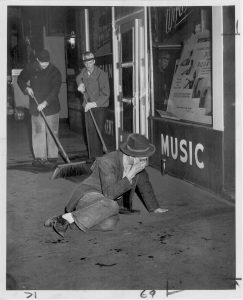

Divena wasn’t the only celebrity in town that fall. Weegee, the famous New York photographer, visited Minneapolis and ventured into Skid Row late at night. He snapped a photo of a bloodied man, his hand over his face, sitting on the sidewalk right in front of the Palms. He’s probably just been tossed out of the place and he’s too drunk or stunned or both to get up. Two men with push brooms are behind him, sweeping him off the sidewalk like so much trash. Nobody knows whether he got a chance to see Divena, whose act is advertised in the window.

Photograph by Weegee, 1950. Image is from the Hennepin County Libraries Special Collections.

Any male who approached the bar would quickly be accosted by a female requesting a drink, in exchange, naturally, for conversation. These were the B-girls, who operated in cahoots with the bartender to encourage as much spending as possible by the customers. She would get a cut, of course.

The owner of the Persian Palms was Harry Smull, a Russian immigrant who built a small liquor empire in Minneapolis, despite a city ordinance that said an individual could only own one liquor permit. That was an effort to keep the liquor business as clean as possible, by discouraging monopolies or mob control. It failed utterly. People like Smull registered the permits in the names of relatives and employees, and for the most part the aldermen and the police, often paid for their courtesy, looked the other way.

That is, until 1961. That year, the redevelopment project that would wipe away Skid Row and 40 percent of downtown Minneapolis was underway. The city was also determined to clean up the liquor business, so they rounded up dozens of liquor permit holders, including Smull, on charges of violating the one-permit rule. A judge eventually threw out all of the charges, and determined that ordinance was illegal.

Despite skepticism from some council members, who welcomed the demise of the Persian Palms, the liquor license was transferred to a bar called the Copper Squirrel on Hennepin Avenue. Yet the Palms endures in the city’s collective memory. It was campy, sordid and outright dangerous at times, like the neighborhood around it. And at the same time, irresistible.