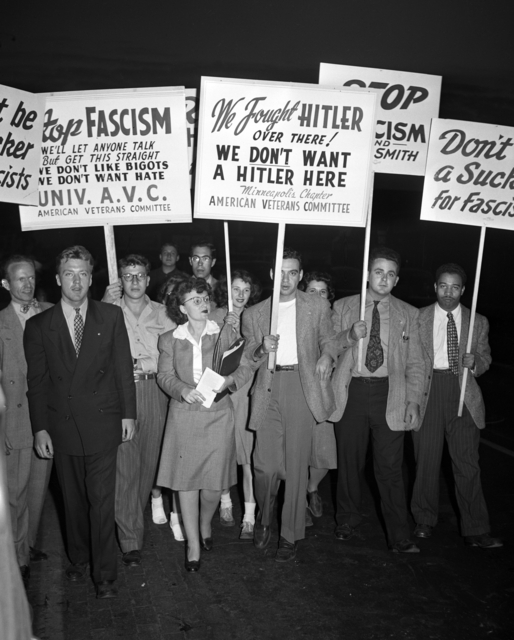

“We Don’t Want a Hitler Here”

In August, 1946, one year after World War II came to a close, hundreds of demonstrators converged on downtown Minneapolis to protest the man best known for promoting fascism in the United States.

Gerald L.K. Smith has been forgotten today, having been long consigned to the proverbial “dustbin of history,” where discredited leaders and wrong-headed ideas from all eras all go to molder.

But in 1946–even in the fresh aftermath of a global war against fascism–Smith was able to command a committed group of followers who feared a Communist-Jewish-African-American threat to the United States.

Smith was the Donald Trump of his time. His contemporaries compared him to Hitler.

Starting in the 1930s, Smith attached himself to various organizations and movements that reflected his xenophobia, racism and anti-radicalism. First, he pledged allegiance to Huey Long’s “Share Our Wealth” movement. Then, he joined the avowedly fascist “Silver Shirts” and finally the isolationists of the “America First” group, which sought to distance itself from Smith’s overt racism.

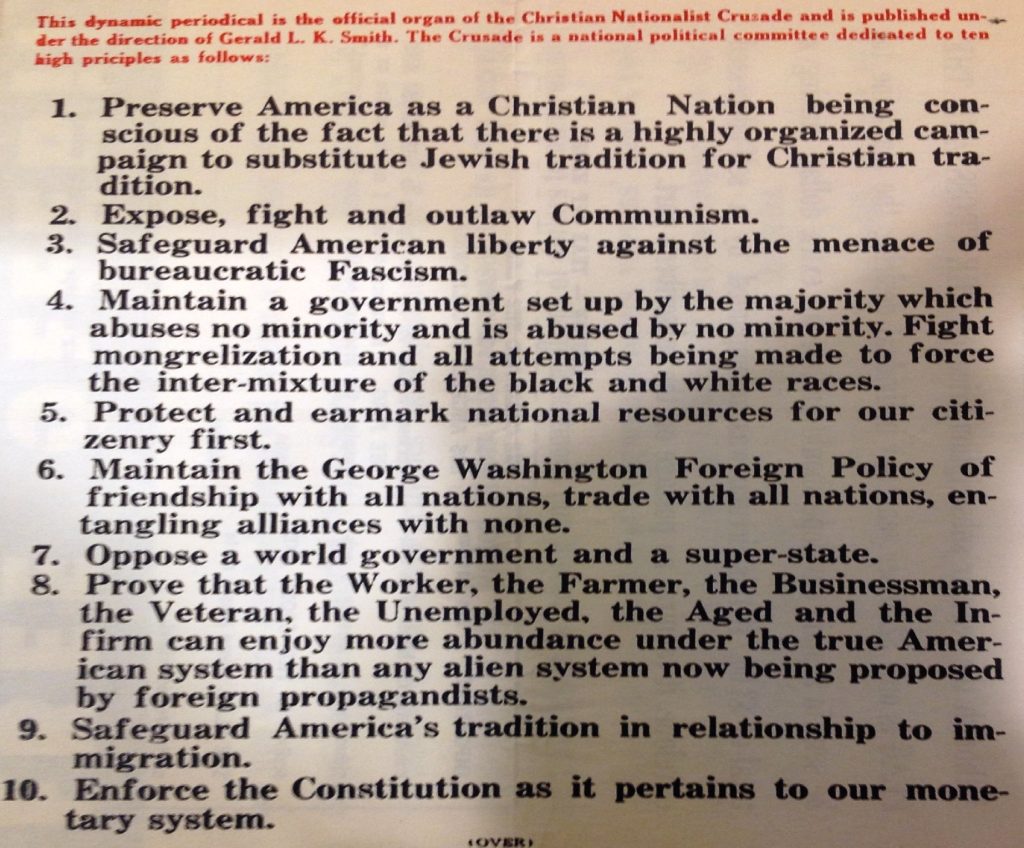

A charismatic leader, Smith decided to claim the limelight for himself. He created his own political party, launching a bid to be president in 1944. This campaign built a popular following for his “Christian National Crusade.” His platform promised to “Preserve America as a Christian Nation” and pledged to fight racial “mongrelization”; the growing influence of Jews; efforts to lift immigration restrictions; Communism and all forms of political radicalism.

Gerald L.K. Smith’s Platform for a “Christian Nationalist Crusade.” From the records of the Jewish Community Relations Committee at the Minnesota Historical Society.

Smith had a strong following in Minneapolis, which was known in these years for its anti-Semitism and political polarization, which had intensified in the wake of the 1934 Truckers’ Strike. This conflict sparked a civil war in Minneapolis between hard-line employers and workers seeking union recognition. This violence prompted at least some observers to worry that Minneapolis would serve as the launching pad for a radical revolution during the 1930s.

Smith drew on these fears during his regular visits to the city in the dark days of the Great Depression and World War II, when he attracted hundreds of supporters. Yet ultimately he had fewer friends than foes, who included labor activists, political radicals, civil rights activists, those determined to fight anti-Semitism and plain old liberals. In these circles, Smith was known as “Hitler’s Mouthpiece in Minneapolis.”

In 1946, some of the more militant elements of this anti-fascist coalition resolved that the time had come to use direct action to confront Smith. Over the protests of established civil rights organizations like the NAACP and the Minnesota Jewish Council, the American Veterans’ Committee worked with the Socialist Workers’ Party and various labor unions to organize a massive protest intended to “force the would-be Silver Shirts out into the open.” They decided to picket Smith’s recruiting rally in Minneapolis, warning that he sought to muster “totalitarian methods against human rights and democratic liberties.”

On August, 21, young veterans gathered at the University of Minnesota and then moved to downtown Minneapolis, where they carried picket signs that declared: “We Fought Hitler Over there! We Don’t Want a Hitler Here.” They called on their fellow citizens to stand fast against fascist ideals: “We Don’t Like Bigots, We Don’t Want Hate.”

The demonstration devolved into fisticuffs after protesters tried to prevent Smith from speaking to the crowd in the Leamington Hotel ballroom. The national media focused on this violence, dismissing the anti-fascist protest as a “brawl.”

The fracas, according to Mayor Hubert Humphrey, illuminated the danger of political extremism. The liberal mayor used this episode to solidify his standing with the city’s conservative business community. He condemned both the picketers and the Smith supporters, positioning himself as the voice of moderation, a palatable alternative to political zealots “who enjoy rabble rousing” and seek opportunities to “disturb the peace.”

Humphrey and his liberal allies in the political establishment believed that if Smith and his ilk should be ignored. Attention would just feed the beast. This may have been true. But the Americans shown here–many of whom had spent years fighting a global war against fascism– were not willing to take that chance.

Images are from the collections of the Minnesota Historical Society. Sources for the text are from Folders on Gerald L.K. Smith, Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota Papers, Box 47, 48, 50, Minnesota Historical Society; Hubert H. Humphrey Papers, Mayoralty Files, 1945-1948, Box 20, Folder: Smith, Gerald L.K. Smith, Minnesota Historical Society.